Most traders don’t think about data until it disappears.

A Google Drive link goes dead. A Telegram group gets deleted. A research PDF you were sure you saved is suddenly “not found.” Even worse, an exchange or app you relied on changes the rules, blocks your region, or locks your account, and you realize you never truly owned the information you thought was yours. In crypto, we talk endlessly about ownership of money. But the uncomfortable truth is that most people still don’t control the thing that matters just as much: their data.

That is the real purpose of Walrus. Not “cheap storage.” Not another token narrative. Walrus is a bet that the next decade will treat data like property, and that users will demand the same kind of sovereignty over their files that crypto promised for their capital.

Walrus is a decentralized storage network built in the Sui ecosystem, designed specifically for large files and “blobs” of data. Think videos, PDFs, research datasets, AI training files, on-chain app history, and anything too heavy to be stored directly on a blockchain. A blockchain is excellent at proving that something happened. It is terrible at holding the thing itself. Walrus is built to solve that gap by splitting data, distributing it across independent storage providers, and making retrieval verifiable without needing to trust a single company.

To understand why “control” is the key word here, it helps to separate two ideas that people often mix up: convenience and ownership. Centralized storage is convenient. Upload file, share link, done. But it comes with hidden dependency. You are renting access, not holding property. Your data exists inside someone else’s rules: their compliance policy, their ban list, their outages, their pricing, their business incentives. And when those incentives shift, you shift with them.

Walrus flips the default. If data is stored on a network instead of a company, the user is not asking permission to exist. They are paying for a service that cannot be quietly revoked by a policy update. That sounds philosophical until you live through it.

Here’s a real-world situation that traders and investors will recognize. Imagine you’ve spent two years building a trading system. You’ve got cleaned datasets, historical order book snapshots, strategy notes, bot configs, execution logs, and performance archives. All of it sits in a few cloud folders. It’s fine, until one day your account gets flagged or locked. Maybe it’s an automated false positive. Maybe it’s a region compliance issue. Maybe you forgot a payment method. In that moment, you are not “temporarily inconvenienced.” You are operationally disabled. Your edge isn’t just your strategy. Your edge is your stored history. Without it, you are starting over.

Walrus is trying to make that kind of lockout structurally harder. Not impossible in every scenario, but harder by design, because storage is provided by many nodes, not a single gatekeeper.

From an investor lens, what matters is that Walrus has a clear economic model tied directly to usage. WAL is the payment token for storage on the protocol, and Walrus specifically describes a mechanism designed to keep storage costs stable in fiat terms over time, rather than forcing users to take raw token volatility as a storage risk. That’s not a minor design detail. It’s the difference between “this works for speculation” and “this can be a real utility layer.” If storage costs swing wildly, serious users won’t commit. Stable cost design is how you get long-term involvement.

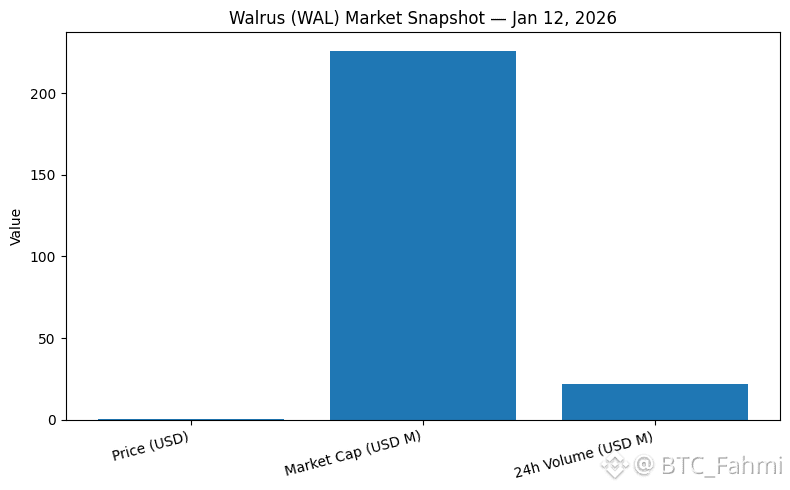

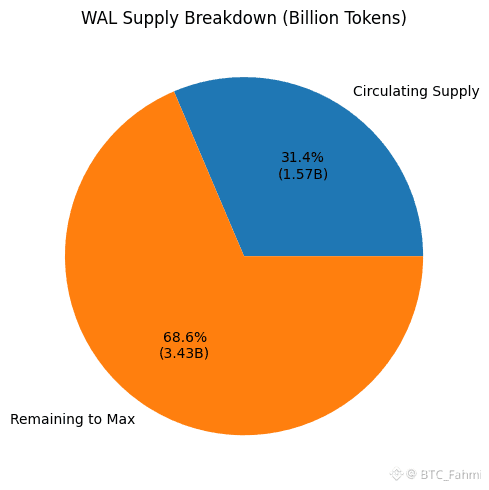

On today’s market data (Jan 12, 2026), WAL is trading around the mid-$0.14 range. Bybit shows about $0.145 with a market cap around $228M. CoinMarketCap lists a market cap around $225M with 24h volume ~$20M–$24M, circulating supply ~1.57B WAL, and max supply 5B WAL. CoinGecko is in the same zone for market cap (~$231M). The important takeaway isn’t the exact number. It’s that WAL has meaningful liquidity for a mid-cap infrastructure token, which makes it tradable, but also volatile enough that narratives can temporarily overpower fundamentals.

The long-term trend that matters here is not “decentralized storage” as a category. The trend is that data is becoming the most contested asset class in the world. AI intensified that. Everything is training material. Everything is a dataset. Everything is a potential product. That creates a tension: users generate data, but platforms extract the value. Walrus is positioned as infrastructure for a world where users and builders can store data in a way that is portable, programmable, and not locked inside one company’s walls.

My opinion, as someone trying to look at this like a trader but think like an investor, is that this is the kind of project where the token only becomes “real” when the boring part happens: sustained usage. Storage is not exciting. That’s actually the bullish part. If Walrus succeeds, it won’t be because people got emotional on Twitter. It will be because builders quietly chose it, month after month, because it worked and because the economics stayed predictable.

The risk is obvious too. “Giving control back to users” is not a marketing feature. It’s a behavioral change. Most people default to convenience. They won’t move until pain forces them, or until the decentralized option feels just as smooth as the centralized one. Walrus has to win on product reliability and developer adoption, not ideology.

But if you want the cleanest, most neutral way to frame Walrus as a trade or investment, it’s this: Walrus is not selling storage. Walrus is selling independence. And in a market where access can be revoked overnight, independence is a product that becomes more valuable the longer you stay in the game.