When I first looked at Walrus, I expected the usual storage conversation to show up quickly. Faster reads. Lower costs. Bigger numbers. Instead, what kept surfacing was a quieter choice that doesn’t fit neatly into performance charts. Walrus is intentionally giving something up, and that trade-off sits right between redundancy and speed.

Most systems avoid admitting that choice exists. They talk as if you can have infinite copies of data and instant access at the same time. In practice, you rarely do. Walrus makes that tension visible, and that honesty is part of why it feels different.

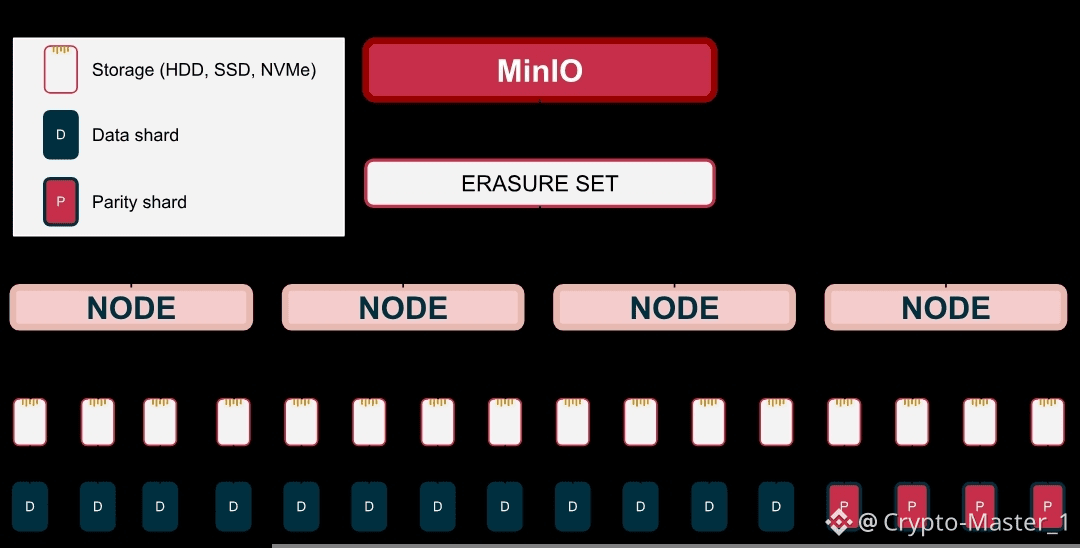

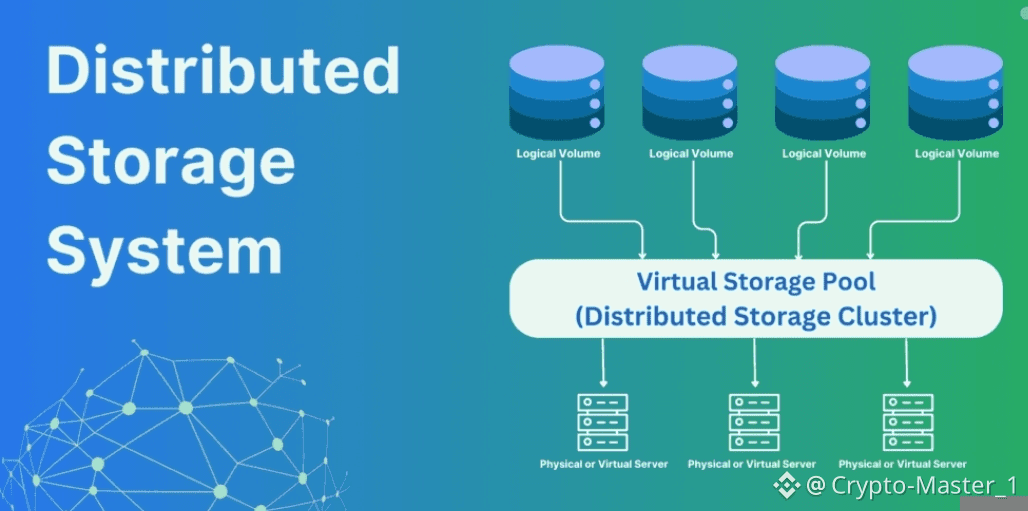

On the surface, Walrus stores data using erasure coding across a distributed network of storage nodes. Right now, that network started mainnet life with more than 100 active nodes, which matters because redundancy only works when there’s real diversity underneath. Data is broken into fragments and spread so that only a subset is needed to reconstruct the original file. This means the system can lose nodes without losing data. That’s the redundancy part.

What’s less obvious at first is what that choice costs. Retrieving data requires coordination. Fragments need to be gathered and reassembled. That process takes time. Not a dramatic amount, but enough to matter if you’re benchmarking against centralized storage or highly optimized caching layers. Walrus accepts that friction rather than pretending it doesn’t exist.

Understanding that helps explain the design philosophy. Walrus isn’t chasing the fastest possible read. It’s chasing the most reliable long-term availability. The system assumes nodes will fail, disconnect, or disappear over time. Redundancy isn’t a backup plan. It’s the foundation. Speed becomes a variable that’s managed, not maximized.

That foundation shows up again in how epochs work. Walrus operates in fixed time windows measured in weeks. Each epoch gives the network a chance to reassess data placement and integrity. On the surface, this looks like routine maintenance. Underneath, it’s a mechanism for keeping redundancy fresh. Old assumptions are replaced regularly. Data is re-encoded and redistributed before decay sets in.

The cost of this approach is latency variance. A file that’s rarely accessed might take slightly longer to retrieve than one sitting in a hot cache. Walrus seems comfortable with that. The design favors consistency over peak performance. In a market that still rewards speed metrics heavily, that can look like a weakness.

Yet context matters. Blockchain infrastructure is no longer serving only short-lived transactions. AI workloads, historical audits, and long-term data records are becoming more common. These use cases care less about milliseconds and more about guarantees. When data needs to be available months later, redundancy starts to outweigh speed.

Pricing reinforces this trade-off. Walrus uses epoch-based pricing rather than dynamic per-access fees. That means costs remain steady across a defined period. Builders don’t get punished when demand spikes elsewhere. The flatness of that pricing curve isn’t exciting, but it’s revealing. It tells you the system is designed for planning, not opportunism.

There’s a subtle risk here. If developers chase speed above all else, Walrus may feel slower by comparison, even if it’s doing more work underneath. Benchmarks rarely capture maintenance, verification, or resilience. They capture how fast something responds once. Walrus optimizes for how well it responds over time.

I found myself thinking about this when looking at other networks that emphasize instant availability. Many rely on aggressive replication or centralized coordination to achieve speed. That works until it doesn’t. When load increases or nodes fail, the system either degrades sharply or requires manual intervention. Walrus is betting that slower, steadier responses create fewer emergencies later.

That bet isn’t without uncertainty. Early signs suggest developers building long-lived applications appreciate predictability. But market incentives change. If attention swings back toward short-term performance metrics, systems that trade speed for redundancy risk being overlooked. This isn’t a technical failure. It’s a narrative one.

Meanwhile, the broader pattern across infrastructure is shifting slowly. We’re seeing more emphasis on lifecycle thinking. Systems are judged on how they age, not just how they launch. Redundancy becomes a sign of maturity rather than inefficiency. Walrus fits that pattern, even if it doesn’t advertise it loudly.

Another layer to this trade-off is psychological. Redundancy feels invisible when it works. Speed feels tangible. Users notice fast responses immediately. They notice redundancy only when something goes wrong elsewhere. Walrus is investing in a feature people don’t celebrate until they miss it.

That invisibility can be frustrating in the short term. It’s harder to generate excitement around resilience than around performance spikes. But over time, systems built on redundancy tend to accumulate trust quietly. They fail less often. They demand less attention. That texture matters.

Looking ahead, this balance between redundancy and speed feels like a preview of where infrastructure debates are going. As applications become more data-heavy, the cost of losing information increases. Speed still matters, but not at any price. Walrus is choosing to anchor itself on durability and accept that some use cases will look elsewhere.

If this holds, the projects that last won’t be the ones that chase every performance benchmark. They’ll be the ones that decide what they’re willing to give up. Walrus gives up a bit of speed to make room for redundancy that doesn’t blink.

The thing worth remembering is this. Anyone can promise fast access when everything is working. It takes a different mindset to design for the moments when it isn’t, and to accept that speed is sometimes the price of staying whole.